Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

On March 19, 1864, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon about women and the Civil War.

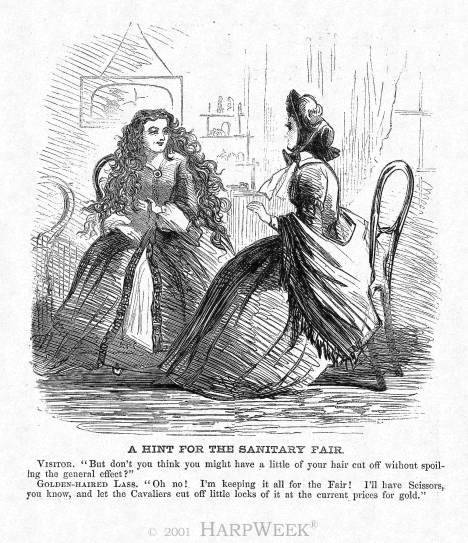

"A Hint for the Sanitary Fair"

Visitor. "But don't you think you might have a little of your hair cut off without spoiling the general effect?"

Golden-haired Lass. "Oh no! I'm keeping it all for the Fair! I'll have Scissors, you know, and let the Cavaliers cut off little locks of it at the current prices for gold."

Artist: unknown

This unsigned Harper’s Weekly cartoon about the upcoming Sanitary Fair in New York City reveals one of the important roles which women played during the Civil War.

On April 22, 1861, a week after the Civil War began, Henry Raymond, founder and editor of The New York Times, placed a notice in his newspaper urging women to meet with his wife at their home on Ninth Street to form an organization "for the purpose of preparing bandages, lint, and other articles of indispensable necessity for the wounded." Women across the North followed their lead by gathering in homes and churches to fulfill the Union’s urgent need for supplies.

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the country’s first female physician (M. D., 1849), began training women at New York’s Bellevue Hospital for work as army nurses. On April 26, she and Louisa Lee Schuyler organized a meeting of 4000 women at Cooper Union to found the Women’s Central Association of Relief for the Sick and Wounded of the Army. Its leaders wanted to expand it into a national organization modeled after the British Sanitary Commission, established during the Crimean War (1853-1856), which sought to alleviate disease caused by the unsanitary conditions of war. Unable to interest federal officials in their cause, the women turned to sympathetic male colleagues.

On May 15, 1861, Henry Bellows, a Unitarian clergyman involved in public health issues, led a delegation of male physicians to Washington on behalf of the women’s group. President Abraham Lincoln was at first reluctant, arguing that the proposed organization would be like an unnecessary and cumbersome "fifth wheel to the coach." He relented, however, and signed the order establishing the United States Sanitary Commission on June 13, 1861. Bellows served as its president, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted as its secretary, and diarist George Templeton Strong as its treasurer. By 1863, there were 7,000 local affiliates throughout the North. The New York Sanitary Commission was headed by George Shaw, the father-in-law of Harper’s Weekly editor George William Curtis.

Although the Sanitary Commission’s officers and most of its paid agents were men, the vast majority of its tens of thousands of volunteers were women. The women collected food, clothing, bandages, and medicine for Union troops, served as volunteer nurses in army hospitals and camps, furnished free room and board to furloughed soldiers traveling to or from the warfront, and raised money through bazaars called "Sanitary Fairs." The highly effective Sanitary Commission collected nearly $6 million during the war, as did a similar (and somewhat rival) organization, the Christian Commission.

During 1864, Harper’s Weekly highlighted the Sanitary Commission Fairs being held in various cities, especially the one in New York. Editorials, news stories, illustrations, and cartoons gave readers an understanding of the purposes, activities, accomplishments, and even the physical layout of these social events which combined entertainment and education with philanthropy. The historical artifacts displayed at the Sanitary Fairs helped create and perpetuate an historical consciousness among Americans. In this cartoon, the second speaker (on the left) is planning to sell snippets of her long, blond hair at a high price—"the current prices for gold"—to men at the fair.

The Sanitary Commission’s popularity with Union troops and its proven efficiency gave it substantial political influence in Washington, even though the private organization’s official powers were only vaguely defined as investigatory and advisory. Commission president Bellows drafted a bill (passed in April 1862) which allowed the surgeon general to ignore the seniority system in the Medical Bureau and to appoint medical inspectors in the field. The Sanitary Commission’s own inspectors submitted detailed reports on the poor sanitary conditions in Union army camps and in Confederate-run prison camps. The Sanitary Commission outfitted several steamships, transferred to them by the government, into floating hospitals, and they pioneered the use of hospital trains and a field ambulance corps.

President Lincoln also named the Commission’s choice, 33-year-old William Hammond, to become the new U. S. surgeon general. Impressed by the female volunteers, Hammond issued a directive requiring that one-third of the army hospital nurses be women. By the end of the Civil War over 3000 women had served as paid nurses, marking the beginning of the transformation of the profession from male- to female-dominated.

Robert C. Kennedy

Image and text provided by HarpWeek.This information was originally published in the New York Times Learning Network.