Elizabeth Blackwell

"Blackwell in Residence: A Legacy Reborn"

Pulteney Street Survey

Fall 1994

By Laurie Fenlason

In a community with a history of modesty, on a campus spare of monuments, the installation of an 800-pount, outdoor, larger-than-life bronze sculpture near one of the Colleges’ most-traveled walkways could hardly be expected to go unnoticed. The fact that the sculpture depicts a woman, as, perhaps, fewer than 50 public monuments in this country do , and a signal figure in the Colleges’ history, has only added to the pride and celebration greeting the arrival of Prof. A. E. Ted Aub’s "Elizabeth Blackwell" at Hobart and William Smith.

|

|

Taking Shape An early sketch, developed into a 16-inch wax model, helped Aub refine the figure's seated position, he said, to reflect Blackwell's "quietness and strength." (Photo: Clayton Adams) |

The first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, Blackwell came to Geneva in 1847 to study at Geneva Medical College, an ancestor to Hobart College and the only institution that would admit a female ‘pre-med’ to its all-male ranks. In a dedication ceremony for the sculpture on October 1, held in conjunction with the Kick-Off celebration for the Colleges’ capital campaign, President Hersh underscored the sculpture’s particular resonance for an institution defined by a coordinate philosophy.

"We are colleges at which gender is both a question and an answer," he said. "Elizabeth Blackwell opened to women an important, previously male-dominated profession , to her abiding credit and, by association, to ours."

Reflecting the breadth of Blackwell’s legacy, a number of distinguished guests joined the 200 alumni, alumnae, faculty, students and friends gathered for the dedication at the sculpture site near the southwest corner of the Quad. They included Blackwell’s grandnephew; a representative from the church in Kilmun St. Munn’s, Scotland, where Blackwell is buried; and administrators from the State University of New York Health Science Center in Syracuse, which traces its founding to Geneva Medical College.

Dean of Faculty and Provost Sheila Bennett, noting that the Colleges have "deeply embraced the name and memory of Elizabeth Blackwell" through the national awards and pre-first-year summer science scholarships that bear her name, said that pride in an exemplary graduate explains only part of the attachment.

|

Sneak Preview. (Above) In December, 1993, various administrators, architects, and other onlookers gathered to evaluate the location and scale of a full-scale, styrofoam model of the sculpture. (Photo: Clayton Adams)

|

|

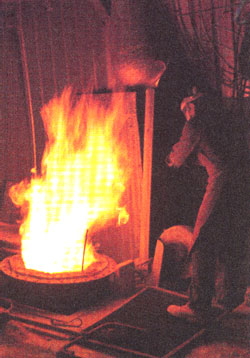

Iron in the Fire. Dexter Benedict, metal sculptor and owner of Fireworks Foundry in Penn Yan, N.Y., heats 150 pounds of bronze ingots to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit in a gas-fired blast furnace. The final sculpture required eight separate pourings of the molten alloy. (Photo: Clayton Adams) |

|

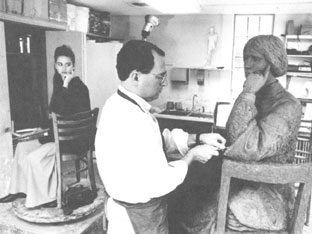

Living History. Three models, including Patricia Nolan, posed for Aub over the three year period required to complete the project. Aub describes the final result as resembling "all of them and none of them." (Photo: Geneva Brinton) |

"I believe we celebrate Elizabeth Blackwell because she represents us at our best." She said, "as a real and tangible emblem of an institution that not only seeks to recognize and meet the need of women, but realizes that, in doing so, we recognize the worth of individuals, as individuals, and the worth of education for lives of service."

For Aub, a member of the Colleges’ faculty since 1981 and an award-winning sculptor, the Blackwell project reflects more than four years of work as well as the vision and support of two administrations. For even an accomplished sculptor of the human body, the interpretive skills required in depicting the historical figure were considerable.

"For any artist, creating a portrait from life is a challenge," Aub explained. "Creating a sculpture larger than life, of the full figure, seated, poses additional challenges. And doing all of this as a posthumous portrait was perhaps the most daunting prospect of all."

Working from the few photographs of Blackwell available, as well as her diaries and biographical records, Aub set out to render her as she might have looked as a student in Geneva. "I thought that depicting her as a youthful figure might provide a common bond between this 19th-century woman and our students of today," he explained.

I also felt it was important for the sculpture of her to depict the ideals of youth," he added. "After all, it was, perhaps, her stubborn naivete that kept her going in the face of formidable resistance."

To create the complex piece, Aub employed an ancient casting technique, perfected by the Greeks, involving an alternating series of positive and negative impressions in clay, plaster, wax, and ultimately, bronze. The method is referred to as the lost-wax technique because a wax ‘positive,’ embedded in a mold, is melted away in a firing kiln, creating a void in which molten bronze is poured to form a cast. From the original clay model of Blackwell, Aub took a 30-piece plaster mold; it was, in turn, used to create a dozen wax-cast sections, which were later transformed into exact bronze replicas. Ultimately, the bronze sections were welded together to form the whole.

Although Elizabeth Blackwell is the first historical figure Aub has sculpted professionally, he recalls creating small-scale statues or busts of mythological and historical figures—Julius Caesar, Zeus, Abraham Lincoln—while still in elementary school. "Rather than write a paper about a famous person, I would ask my teachers if I could make a sculpture of the person or character instead," he said. "They almost always agreed."

As a painting major in college and graduate school, Aub extended his interest in portraying the human figure into the third dimension, taking elective courses in figure sculpture that were often scorned by art students drawn to the abstract styles of the mid-1970s.

While on a painting fellowship at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1978, Aub discovered his true calling. "I woke up one morning and realized I wasn’t a painter," he recalls, "but a sculptor.

"I admitted to myself that I wasn’t interested in color," he explains, "but in form, space, scale, and dimension, all the elements of perception that aren’t as much painterly as sculptural."

Although his exhibited work is often described as abstract figuration, reflecting the formal and surreal influences of Elie Nadelman, Fernando Botero, and René Magritte, Aub was drawn to the realistic and monumental Blackwell project by the character of Blackwell herself.

"I don’t think I could sculpt someone I didn’t respect," he said. "The reason I liked this project so much is that I liked the person I found when I researched her, and the person who began to take shape. I believe strongly in what she stood for, particularly the values of fairness and social justice. That made it a worthwhile project."

|

|

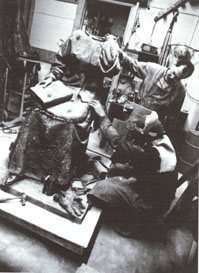

Piece Work. Metal flashings, embedded in the clay model, served as dividing lines for 30 plaster sections of the mode, designed, as Aub explained, to "come apart like a giant, 3-D jigsaw puzzle." (top) Building up the inner surfaces of the plaster mold with sculpting wax, Aub creates the second positive state of the process. The sculpture goes from clay to wax to bronze (bottom). (Photos: Geneva Brinton)

|

|

|

|

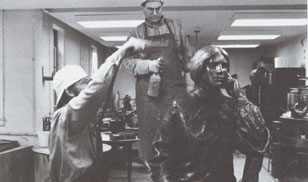

Form Fitting. Reassembling the 10 bronze casts for welding required "some pushing and pulling," Aub explained, to compensate for expansion and contraction in the pouring process. (top) With the sculpture in a hoist, Aub and Benedict grind, sand, and file the surface (bottom). (Photos: Geneva Brinton)

|

|

|

|

|

Finishing Touches. Delivered from the foundry to Aub's studio in the Carriage House on the grounds of Houghton House, the 800-pound sculpture is prepared for display (above). Ammonium sulfide applied to the heated surface of the bronze imbues a reflective patina of rich color to the surface, speeding the natural process of oxidation (below). (Photos: Geneva Brinton).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pride of Place. Congratulating Aub at the sculpture’s dedication, President Hersh said he found it "immensely satisfying and entirely appropriate that the first and only representation of a human figure on this campus is that of Elizabeth Blackwell. That says so much about who we are and what we value." (Photo: Clayton Adams) |

|

Grounded in History. A bronze plaque, embedded in the walkway leading to the sculpture, carries an inscription composed by Dan Ewing, professor of art, noting Blackwell’s historic ties to the Colleges. Engraved in the sculpture’s granite base is an excerpt from a letter Blackwell wrote from Geneva in 1847, selected by Professor of English Deborah Tall: "I cannot but congratulate myself on having found at last the right place for my beginning." (Photo: Geneva Brinton) |

|