The Pulteney StreetSurvey

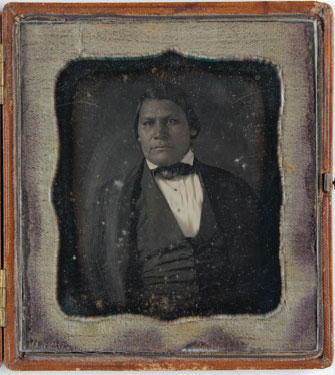

The National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center at the Smithsonian Institution holds a daguerreotype depicting Wilson, ca. 1852–55.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN ARCHIVES CENTER, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION (NMAI.AC.405). PHOTO BY NMAI PHOTO SERVICES.

Scientific Methods

MEDICAL HISTORY.

Dr. Peter Wilson, 1844, was the first Indigenous graduate of Geneva Medical College and likely the first Native American to earn a medical degree. A member of the Cayuga Nation, Wilson grew up and was educated at a Quaker school on the Buffalo Creek Reservation in Erie, N.Y. When he arrived at Geneva’s fledgling medical school in 1842, he was already a “skilled politician like his uncle Red Jacket,” writes Mary Hess, who taught at HWS from 2005 to 2011 and later at SUNY Oswego. “Wilson was a powerful, passionate orator and also a translator for the U.S. government; just as significant, and his calling card in the white world, was his astonishing scientific versatility: physician, dentist, surgeon, as well as a lawyer and diplomat.”

Wilson was a signatory to the Buffalo Creek Treaty of 1838, which, as part of the U.S. government’s Indian removal policies, led to the migration of Seneca and Cayuga residents of Buffalo Creek to Oklahoma. Amid concerns over federal fraud, Wilson soon after began a 20-year lobbying effort to reverse and rectify the treaty, restore Native residents to the Cattaraugus and Allegheny reservations, and ensure they were compensated for the Buffalo and Tonawanda reservations.

As a physician and surgeon, Wilson practiced at Bellevue Hospital in New York City and on the battlefield during the Civil War. He eventually returned to the Cattaraugus reservation, where his last years “were likely difficult” due to a stroke, as Hess explains in the spring 2020 issue of The James Fenimore Cooper Society Journal. Despite Wilson’s renown as an orator, his death in 1872 “was briefly remarked upon in a Buffalo newspaper as the passing of an old chief.” Though he endured the “personal strain” of “negotiating two worlds” — including the “fraught endeavor” of the 1838 treaty — Hess concludes that Wilson’s life was one “of service, both to his patients and to his Cayuga and Seneca people.”

FIELDNOTES.

For well over a century, scientific inquiry has taken students and faculty from campus classrooms into the surrounding environment — and sometimes farther afield. Studying invasive species, Professor of Biology Meghan Brown (center) has traveled to Italy, Guatemala, Australia and New Zealand, and back to Seneca Lake, bringing new data, techniques and perspectives on troublesome non-native plants and animals. In 2016, she led a team of interdisciplinary researchers in Cuba to investigate why the island nation has fewer invasive plant species compared to its Caribbean neighbors. Brown returns in December 2022 with Professor of Spanish and Hispanic Studies May Farnsworth to guide alums as they explore Cuba’s ecology.

THE EYE OF THE STORM.

THE EYE OF THE STORM.

Documenting severe weather on the horizon near Anton, Colo., during a 2017 geoscience field course with Professors Neil Laird and Nick Metz. The core faculty of the atmospheric sciences program, Laird and Metz regularly lead students on the hunt for supercell thunderstorms and tornados — that is, when they’re not compiling an unprecedented lake-effect snow database. Or mentoring students through the Northeast Partnership for Atmospheric & Related Sciences, which attracts undergrads from across the country to research weather and climate phenomena with HWS students and faculty. Over the past 20 years, these developments have distinguished the Colleges as a hub for atmospheric research and education. (Notable: Albert J. Myer, 1847, who organized and commanded the U.S. Army Signal Corps during the Civil War, is considered the father of the U.S. Weather Bureau, a precursor to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.)

OBSERVE AND REPORT.

The first astronomy observatory on campus, built between 1869 and 1870, was located roughly where Gulick Hall now stands. Today, students and faculty explore the cosmos at the Richard S. Perkin Observatory near Houghton House.