HWS News

1 August 2023 • Alums • STEM Pocket Miracles

Cataracts are the leading cause of blindness worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control. At the same time, a 15- to 20-minute cataract surgery can restore eyesight by the next day. But while cataract surgery is common in the United States, it is hard to come by in many countries.

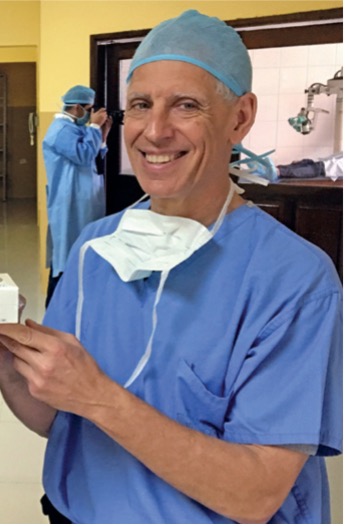

Dr. Kozarsky and his colleagues perform cataracts procedures in Honduras, where he has been serving patients pro bono for more than three decades.

“Cataract blindness is a huge issue, particularly in developing countries,” explains ophthalmologist Dr. Alan Kozarsky ’74, one of the leading vision correction specialists in the U.S. Kozarsky is an expert in front-of-the- eye surgeries such as cataract procedures, and for more than 30 years has been carrying out medical outreach missions to Honduras.

“Cataract surgery is one of these really amazing pocket miracles in medicine,” he says. “You can change someone’s life in minutes.”

In Honduras — one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere and among the most violent in the world, according to the United Nations — access to healthcare varies widely by socioeconomic status and proximity to urban areas; doctors are in short supply.

Kozarsky first learned about the medical need in Honduras in the early 1990s when a colleague at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital, Steve Wilkes, shared his own medical outreach experiences there. Soon, Wilkes was returning from Honduras accompanied by eye patients for Kozarsky to treat in Atlanta. “We did that for a few years,” Kozarsky remembers. “And then I said, ‘I probably should pay them a house call now.’ And that’s how I got started going to Honduras.”

As a student, Kozarsky had learned to pilot planes with the Hobart Flying Club. Over the years, his interest and skill only grew, and by the time he was leaving for Honduras, he not only had his pilot’s license but his own small plane. Flying himself and his team meant “[we] could get on the ground quickly.... Honduras was close by small plane and that made it all very doable and really increased the yield of our missions.”

At first Kozarsky and his team carried out a few surgeries in remote parts of the country, but eventually they realized they could

have greater impact if they worked with an established eye facility. That morphed into closer work with Honduran doctors, with Kozarsky’s team sharing techniques to increase efficiency and levels of care. “Our end game was to get to the point where they wouldn’t need us anymore,” he says. “They would be able to do this on their own, every day, year- around. It’s about sustainability. It’s about scalability. If you can change one life with cataract surgery, why not change thousands?”

“Doing global health care is very complicated. You need to learn the landscape and make sure you’re helping the people who need it the most.”

Over time, the program improved even more as Kozarsky and his colleagues connected with the social entrepreneurship program at Emory University, which helped them grow the eye clinic facility in Honduras, and with Wake Forest University’s medical outreach program, which offers training to Honduran doctors.

“Our little program in Honduras has turned into the largest provider of cataract care in the country,” Kozarsky says. “They perform thousands and thousands of these operations without our help now.”

Even though he’s not needed like he

once was, Kozarsky returns to Honduras every year to perform surgeries and keep connections with local partners strong. “Doing global health care is very complicated,” he says. “You need the support of the locals. You need to learn the landscape and make sure you’re helping the people who need it the most. You have to listen to the medical people there. They can help you find the most needy and deserving and underserved in their country and help you have the most impact. It’s amazing how much you can help humanity that way. There’s nothing that feels better.”

Looking back, Kozarsky says: “At Hobart I learned how to fly. And at Hobart, I learned how to go to medical school. So there are the seeds for the whole thing.”

This story originally featured in the Summer 2023 edition of the Pulteney Street Survey.